A number of you have been asking…You’re waiting for the other shoe to fall. Or for the book to show up as the case may be. Well, it turns out that my book which is in itself a saga now has a saga of its own. And after all why can’t inanimate objects have experiences. Two years ago when I traveled to Europe with a wheelchair, which I named Duncan, I felt as if Duncan, as he headed off into the cargo hold or hung out by the sea, was having his adventures too. Why not my beloved book?

So I shall begin almost at the beginning…

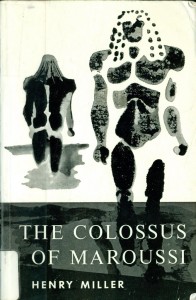

In 1981 while heading to Greece I picked up a copy of THE COLOSSUS OF MAROUSSI. I read it in Corfu and essentially have been reading it and annotating it ever since. Until I read this book, I didn’t know what passion one could bring to writing. It is a kind of bible to me. Or at least it is the book that opened my eyes to the world around me and set me out on a journey into the world in a new way. In search of what Miller himself calls “the finger of mystery.”

The other morning, with snow forecast in the air, I set off for my commute to work. I had Maroussi tucked into my pocket and, as I was leaving, my husband, Larry, told me to be careful. “Don’t lose it,” he said. If he hadn’t said that, it wouldn’t have occurred to me to lose it. After all in my wanderings and in all its wanderings I had never lost it before. But now I heard my father’s voice. One of those admonitations. Don’t carry all of that on the tray. You’re going to drop it. And guess what? You do! You drop it! Don’t lose your book, Larry said. Why would he say such a thing? It’s a book I’ve carried with me on and off for almost thirty years!!! Imagine. How could I lose my book?

On Wednesday while trying to conduct a conference with my wonderful student, James, I began to notice that my book was not in my office. I am sure it was very distracting to James to talk about things that matter to him while I am tearing my office apart. But indeed the book was not there. Slowly I began reconstructing my day and, on my way home with my friend Nelly, it occurred to me that somehow I had left it on the counter where I purchased my iced coffee at Zaros near track 34 at Grand Central Station.

Silently I began to blame my husband. If he hadn’t told me not to lose the book, I’d have it now. (Nelly pointed out that this wasn’t a constuctive way to think of this situation…) By the time I got home I knew I’d left it on the counter at Grand Central and I was determined that the next morning when I went into the city for a doctor’s appointment that I’d go retrieve it.

As I have said before on my blog, I don’t backtrack. I will go out of my way not to return the way I’ve come. It is almost a phobia with me. The way spiders or the dark are for some people. But retracing one’s steps, I’ve decided, isn’t the same. When we backtrack, we return empty handed. We just go around in a circle and come back the way we’d gone. But when we retrace, we retrive what we had believed to be lost. My husband isn’t good at this. He’ll lose his wallet, his keys. Think backwards I tell him. So I retraced my steps.

As many of you who live in the United States know on Thursday we had a blizzard. Still I headed out, but with a detour to the Brooklyn Public Library to find a library copy of Maroussi and met with a snarky librarian who informed me that lesser works of an author are usually in the archives. I could not help but feel insulted not for myself, but for this book which I loved. “This is not a lesser work,” I said. “It is a masterpiece.”

“Go to history,” the librarian said.

In the travel/Greek section which was in history, I found three copies of Maroussi, checked one out and, at last I was on the train. I went to my doctor’s appointment. I was on my way to see the orthopedic surgeon who had treated me since I broke my leg two years ago ice skating in Prospect Park. I like Dr. Isaak. He intrigues me. He has a bit of a mystery about him, even to those who work with him, I’ve learned. No one knows his story. No one knows about his personal life. Yet as Larry said when he walked into my hospital room at four a.m. after I’d shattered my fibula, he has a good handshake.

He had few patients that day. Many had cancelled. Normally I wait hours. I’d brought a backpack full of work and, of course, now my new version of Maroussi. But it was a book I couldn’t write in. I couldn’t scribble the endless commentary I have going in my head between myself and Henry Miller. A man I think I’d hate in life, but I love him, I truly love him, on the page.

Dr. Isaak looked at a new Xray of my ankle and determined that I’d need yet another surgery. A piece of bone has grown over the ankle joint, he told me. “If it was your ankle…” I asked him.

“If it was my ankle,” he said, “I’d take that piece of bone out.” As an interim measure he told me he could inject the joint. I have a lot to do in the next few weeks. My teaching at Sarah Lawrence, a trip to Florida for a writer’s retreat, a trip to Turkey. I agreed.

“Will it hurt?” I asked.

“Not so much,” he told me.

He was right. It didnt’ hurt at all and soon I was on my way in the falling snow and wind (the snowicane we were supposed to have) to Grand Central. My ankle, which I’d had trouble with since my accident bothered me, but not so much. I’d be home soon.

At Zaros, I walked in, holding up the library copy of Maroussi in my hand. “Did anyone find this book yesterday?” The staff of workers – mainly West Indian employees who cut bagels in two for office workers all day long – stared at me.

“But you have the book,” the cashier said.

“Yes, I know, but this one isn’t mine. This is from the library. I left mine here, I think, on the counter just yesterday.”

They all shook their heads until a timid, young woman spoke up. “Sonya got it.”

“Who?” I asked.

“Sonya, she got it,” she said, her eyes looking down.

The manager who was arranging chocolate cakes on the other side of the counter turned to her, his face filled with threatening rage. “What’re you talking about?”

The girl repeated that Sonya had my book.

“No she doesn’t,” the manager said. I turned to the girl who now wouldn’t look me in the eye. “Nobody has your book, Ma’am,” the manager said to me.

“What do you mean?” I looked back at the girl who now wouldn’t look at me. “I’m a teacher,” I told the manager. “I need that book.”

“Nobody has your book.”

I could see that heads were about to roll so I walked away, then paused. It seemed as if the entire staff was conferring. I return to the store. “I’ll offer a reward. I just want my book back. No questions asked,” I whispered to the man who ran the store.

“Call me tomorrow,” he said.

On the way home, as my ankle was stiffening and I was finding it harder and harder to walk, I pondered what had just happened. Clearly Sonya had pocketed the book, thinking who’d come asking for a crumby old tattered paperback like that one. But someone had and the manager didn’t want to admit that someone on his staff had stolen and I didn’t want to get Sonya fired. In fact I liked the fact that Sonya wanted my book. I’d give her a dozen books if she wanted. I’d take her over the bookstore in Grand Central and let her pick out a few. But I wanted my annotated, lifelong Maroussi back.

By the time I got home I couldn’t walk. My doctor hadn’t told me that this would be the case. Well, I thought, in the morning I’ll be fine. But I wasn’t. I woke up and found that I couldn’t walk at all. The injection had done something terrible to my foot and once again, as it had happened to me two years ago, I couldn’t take a step. In the midst of a long, depressing day I phoned. They had my book. It was waiting for me. “Ask for Allison,” the person I talked to said. Then whispered to me, “Allison is a man.”

I’d fully intended to go to Grand Central myself and retrieve my beloved book, but I’ve sent my husband there instead. He has to go that way to work anyway. It is four days and I still can’t walk, but my book is coming home after having his adventures, his trials and tribulations. And he’s returned with what any wanderer likes to come home with. A story of his own to tell. But just an hour ago I received a call. Larry from Zaros. “They have several books here,” he told me, “but not yours.”

“Is Sonya there? Ask for Sonya.” Apparently there were two Sonya’s and none reported for work that day.

I’m coming to accept that my book is gone. Like a favorite stuffed animals to a child or well-worn shoes to a man, this is hard to let go of. I wonder where it is. I hope someone is reading it now. And part of me imagines that whoever has it will track me down and get it back to me. But another part of me worries for its safety. I cannot bear to think of this beloved, tattered volume, tossed in a heap. It was something I’d planned to carry with me my entire life. But if I were to ask Henry Miller himself, I’m sure he’d tell me to just let it go. That is part of the whole point of this book. Miller tells us to pare down. Simplify. Not to need things. He doesn’t need anything. He has no money. He doesn’t own a thing. He doesn’t hold on. But he has an indomitable spirit. And he is passionate about everything in the moment. As he is living it.

But I love this book. I need it around me. Last night I ordered one from Amazon. It feels too soon. I’m still grieving. But there are passages emblazoned in my head and in my heart. I’m not sure that I’ve learned that much about Greece by reading it and I know Miller breaks every rule of writing I try to teach. But it is a book that has taught me so much. It feeds me like food. Desire is in itself an action, Miller tells us. And I know that this is true.

Mary — What a wonderful story! I love it. Will tweet it.

Oh thank you so much!!! xoMary

Okay, you have convinced me. I will order a copy of the book today. There will be a run on that book at Amazon. Also, in the future I will leave my annotated copy of Thoreau’s Journals at home any time my partner tells me not to lose it.

Thanks for a great story and inspiration.